Q: Why did you write this book? What matters to you about it? What effect do you want it to have on readers?

First off, can we agree that everything I say here will be wrong? This is impossible to talk about.

Q: Okay, but same question again.

To enchant, to astound, to console, to provoke…

Q: Can you say a little more please? Throw me a bone here.

I would like readers to enjoy the complex portrayal of complex people together and apart, to gain a sense of breadth and depth by way of the different times and places the book explores, savour a multivalent aesthetic experience as they sink their teeth into many different forms and voices, while being touched by the sadness of the characters’ human plights and the beauty, sentence by sentence, of its rendering.

Q: Right. Maybe we’ll get further if you tell us about how you came to write it?

Probably—let’s be pragmatic. So, I finished a novel, put it to one side, wanted to do something else. Started going through some old stories from under my desk. Some of them were published, some not, some brand new, some of them so old that I only had dusty print outs. Around this time I joined a story group with friends and we’d meet every couple of weeks, so I started reading more short fiction and sharing some of mine with them for their thoughts. Nothing kept happening with the novel, and I spent more time on this growing project—as so often what you do on the side, on a break, takes over your life, perhaps because it doesn’t feel professional and serious, so you can have more fun with it. Then I read George Saunders’ book about Russian short story writers, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, which exploded over my head like a grenade and caused me to think a lot more deeply about what my individual stories were doing, and I plunged back into working on them more deeply. By then I was looking at them together, paring some away, working on others, and I started seeing more and more thematic links, connections, recurring characters, protagonists, a family. I started seeing ways they might grow and change if choreographed, if mosaiced, if juxtaposed, and this work became a big part of my thinking on the project. Then when I felt I’d finished I had an editor, my friend Jane Warren, read it and that changed the project in important ways. Her assiduous advice made me see that I wasn’t nearly done; the quality of her attention made me feel that there was something worth finishing.

Q: I’m curious about something you just mentioned: why linked stories?

I like each thing I write to be in a new genre for me. I’ve published a book of short stories, a historical novel, and a play, and written more speculative and memoiristic works too. I think of linked stories as a genre. In each story you have the play and precision of the form and each one stands by itself; but they call to each other and reflect back on each other in ways that suggest the sweep of a novel. Together I think of them as an album, or as a certain kind of family, that fits together in important ways and doesn’t in others. I like the floating through time this allows, and the variety of voices, the way that some of them are “written” or spoken by different characters, the puzzling quality (I mean the quality of something worth puzzling over) that this allows. When I’m reading I love the experience of making connections, that sense of a larger universe that unexpected links can give: but I also love differences. The other day I found an old notebook entry that said “Write something that changes shape constantly as it goes on,” and I guess that’s one thing I’ve tried to do.

Q: You describe the book as a family, but it’s obviously very concerned with individuals also.

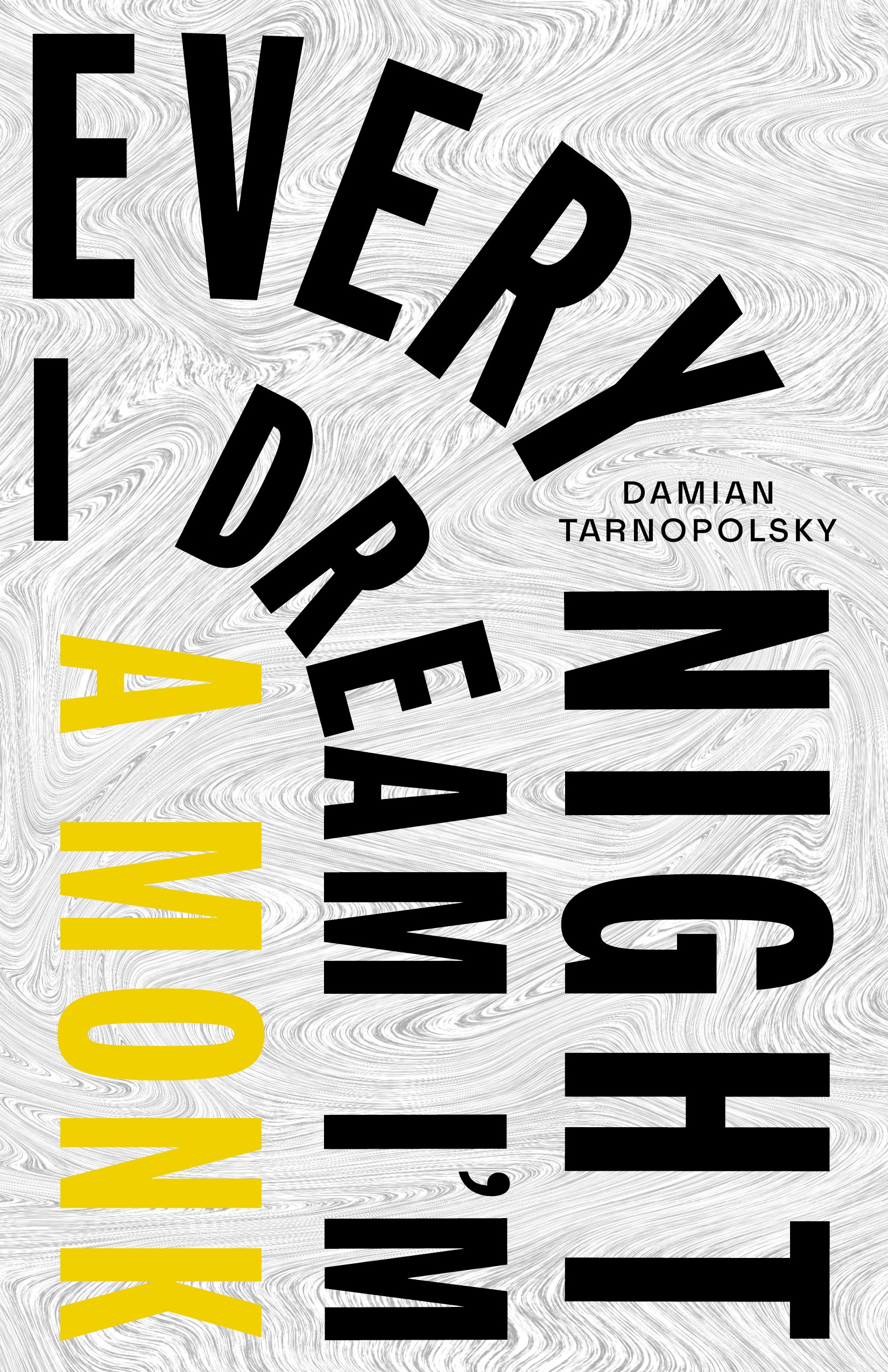

Fair point. While I was writing it I got a little obsessed with ideas about the self: what does it mean to be the same person over time, or not? How fragile and temporary is our sense of self? What do we owe our future selves, how do we relate to our past selves? It’s such a simple thing, that no one talks about much, but it started to seem like a puzzle and a scandal and in part the book is a response to it (while also reflecting my own changes over time: many of these stories are quite old, some of them are brand new). I have so many inarticulate thoughts about this, but they make their way into the book as characters, questions, themes. Is Mark in the book a little trapped by stories he’s telling himself about himself? Why can’t he get free of them? We identify often with our conscious minds, but aren’t we much more than that in our memory and desire, our physical presence, our dreams? And how much of our sense of self actually comes from our connections to the people around us? What happens when they get frayed? A rich internal life can be a blessing, but often, paradoxically, we often feel most ourselves when least conscious, in moments of great passion or awe, I mean at our most animalistic or most transcendent: Every Night I Dream I’m a Monk, Every Night I Dream I’m a Monster.

Q: But there’s some (if I may say) dark, sad, nasty material in the book. Why don’t you write about nice things?

A friend of mine says he can only write at 5am, and that what he writes has to make sense to his 5am self—not his “proper” daytime, 11am self, with its friends and obligations, but the secret self that wants and despairs and hopes and lingers. There’s a lot to that. But I hope that there’s some joy in the stories too, that formally, sentence-by-sentence, though it might seem dark, it’s actually full of love and care. That it’s paying attention and giving sympathy to partial people in difficult moments, I was going to say people who are doing their best, but no, we don’t always do our best, do we? Sometimes we can’t. I hope the book successfully stages the ranting and violence and hate that that suffering can lead to, rather than monochromatically endorsing it. But it’s up to the reader to judge, of course.

Q: You teach in a Narrative-Based Medicine program. What is that, and how does it relate to your fiction?

Part of what I teach is called “narrative competence,” which is encouraging health practitioners to get better at handling stories (their own, their patients’), at being reflective about their place in a certain plot, about the particular words they’re using. And realizing that stories have more agency here than we sometimes realize. Recently the work has given me community, colleagues, stability, and connection that I’ve never had before, and the students are incredibly devoted, thoughtful, hard-working people. It’s very rewarding to spend time with them. It’s hard to teach people to write, really, but I try to show them where some of the interesting stuff is, what some useful questions to ask are, what drawers the tools are in, and how best to use them, and it seems to help them, much of the time, which is satisfying too. I can’t phone it in because the material and the subject matters to me. I don’t know if it’s had a massive impact on my writing, but (cliché approaching) you do learn a lot from teaching, from having to find ways to talk about what you do every day and how you do it. Though as Doris Lessing said, “To write you have to be slightly bored,” and so I have to be quite disciplined about protecting writing time, making sure I have time to be bored.

?! : . , “ ; : - — ” . — “ … - ; …. << !

Q: Sounds neat. Okay, finally a writing question: who are your influences? Where do the individual stories in the book come from?

Oh, so many influences, so many places. A man I saw walking down my street collecting bottles and putting them in a shopping cart one morning; a Pinter play I went to when I was a student; a history podcast I happened on a couple of years ago; helping a friend move house; visiting a college that used to be a mental hospital… But yes, they are stories written over a long time, so there are lots of other books in this book. I love Flights by Olga Tokarczuk for the way it mixes genres and voices and moved around characters and times. I did a PhD on the late modernist novel and love how writers like Elizabeth Bowen and Henry Green put a crunch in every single sentence, and how they even use microscopic details – even punctuation – in unexpected ways to intensify their prose. Samuel Beckett was big for me, and Thomas Bernhard. James Salter for the intensity of his writing about sex and desire, and Lisa Moore, for her floating structures. George Saunders, whom I mentioned, as much for his criticism as his fiction. The lyrical quiet Irish writer John McGahern, Radiohead, Jennifer Egan, Ottessa Moshfegh for her sense of human inexplicability, Cesar Aira for his playful daring, Stanley Kubrick and Christopher Nolan for their perfectionism and variability, Thom Jones’s trillion-volt style… I could go on.

Q: What are you working on now?

You said the last question was “finally.”

Q: Humour me.

That novel I mentioned.